Alaska's rivers are turning orange, and the changes are irreversible

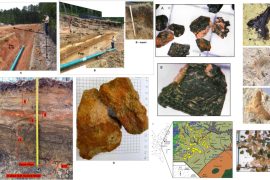

High in Alaska’s Brooks Range, streams that once ran so clear you could drink from them are now the color of rusty tea. The water looks hazy, smells metallic, and can stain rocks orange for miles.

Fish are struggling, insect life is smothered, and the change has arrived with startling speed. Scientists say the culprit isn’t industry. It’s thawing permafrost.

When frozen ground wakes up

For millennia, Arctic permafrost – permanently frozen soil – locked minerals in place. As the region warms, that icy seal is failing. Water and oxygen seep into freshly thawed ground and set off a chain reaction in sulfide-rich rocks (pyrite is a prime example).

The chemistry is textbook: sulfides oxidize, sulfuric acid forms, and the acid leaches metals like iron, aluminum, and cadmium from surrounding rock. Those metals then flush into rivers and streams.

“This is what acid mine drainage looks like,” said Tim Lyons, a biogeochemist at the University of California, Riverside. “But here, there’s no mine. The permafrost is thawing and changing the chemistry of the landscape.”

Astounding changes in water chemistry

A new study zeroes in on the Salmon River, a key waterway in the Brooks Range, documenting just how far the contamination has progressed.

But the authors stress the pattern isn’t isolated. Similar transformations are underway across dozens of Arctic watersheds that share the same mix of geology and thaw.

“I have worked and traveled in the Brooks Range since 1976, and the recent changes in landforms and water chemistry are truly astounding,” said David Cooper, a Colorado State University research scientist and co-author of the study.

The alarm first sounded in 2019. Ecologist Paddy Sullivan of the University of Alaska was flying into the backcountry to study northward-shifting forests when his bush pilot mentioned the Salmon hadn’t cleared after snowmelt – it looked, he said, “like sewage.”

Sullivan’s field observations led to a collaboration with Lyons, Alaska Pacific University’s Roman Dial, and others to trace the cause and measure the ecological fallout.

Toxic metals in Alaska’s rivers

The team’s analysis confirmed a geochemical cascade. Permafrost thaw exposes sulfide-bearing rocks, oxidation generates acidity, and the resulting acid mobilizes a suite of metals.

In small doses many metals are harmless or even essential. But at higher concentrations they become toxic to aquatic life – and the Salmon River’s waters now exceed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency thresholds for several metals detrimental to fish and invertebrates.

Iron is the most visible signal. As iron oxidizes, it forms fine, orange precipitates that cloud the water and coat the streambed. That haze blocks sunlight that algae and aquatic plants need, and the sludge blankets the gravel and cobbles where insect larvae live and fish spawn.

Cadmium is more insidious: it can accumulate in fish organs, potentially affecting predators from Dolly Varden trout and grayling to birds and bears.

Ripple effects in the food chain

For now, the researchers say metal levels in edible fish tissue are not considered hazardous to humans. But indirect risks loom large.

Chum salmon – central to the diets and culture of many Indigenous communities – lay their eggs in clean, oxygenated gravel. When those spaces fill with fine sediment and metal precipitates, the oxygen drops and eggs can suffocate.

Changes in insect communities ripple up the food chain, weakening the foundation that supports juvenile fish and the species that eat them.

Irreversible shift in Alaska’s rivers

Unlike mine sites – where engineers can install liners, drains, or neutralizing systems – these rivers wind through remote, roadless country, and the sources of contamination are everywhere thaw has reached the right rock. There is no single pipe to plug, no settling pond to build.

“Wherever you have the right kind of rock and thawing permafrost, this process can start,” Lyons said. And once it does, it tends to keep going. The only true “off switch” would be for the permafrost to refreeze – an unlikely prospect in a warming climate.

“There’s no fixing this once it starts,” Lyons said. “It’s another irreversible shift driven by a warming planet.”

Fingerprints of global warming

The experts hope their findings will help communities, land managers, and fisheries prepare – by expanding water quality monitoring, identifying vulnerable spawning grounds, planning alternative harvests if runs falter, and adapting management practices as conditions change.

The broader message is sobering. The Brooks Range is about as far from cities and smokestacks as you can get. Yet its rivers are wearing the unmistakable fingerprints of global warming.

“There are few places left on Earth as untouched as these rivers,” Lyons said. “But even here, far from cities and highways, the fingerprint of global warming is unmistakable. No place is spared.”

Rivers once known for their wild clarity are telling a new story – one where ancient ice, long trusted to keep the land’s chemistry in check, is finally letting go.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Image Credit: Taylor Rhoades

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way