Archaeologists uncover a 9,000-year-old quartz tool workshop

A new paper documents a 9,000-year-old quartz tool workshop and a fireplace at the Ravin Blanc X (RBX-1) site in eastern Senegal. The site captures a brief moment in the work of Later Stone Age (LSA) hunter-gatherers. The evidence is preserved, like a time capsule, beneath younger deposits.

Archaeologists, led by Charlotte Pruvost from the ARCAN Laboratory of the University of Geneva, found an exceptionally intact layer with toolmaking debris, a shallow hearth, and sediments that still hold microscopic plant and wood traces.

The excavated area is small, about 269 square feet (25 square meters), yet rich enough to say something meaningful about people who lived at the end of the last big climate swing into the Early Holocene.

Why the quartz tool site matters

West Africa is huge, roughly 2.3 million square miles (6 million square kilometers), yet stratified prehistoric sites are scarce and often disturbed.

RBX-1 gives researchers a clean, well dated context from the Later Stone Age, a period when small, efficient tools and composite hunting gear became the norm.

“The discovery of RBX-1 enhances our understanding of the LSA in West Africa by providing a rare, well-dated stratigraphic context,” wrote Pruvost.

The team reports a tight cluster of activity dated to the early part of the Holocene, the warm interval that followed the Pleistocene.

What the team found

The layer includes a quartz knapping area, about 31 inches (79 centimeters) across, where nearly 1,200 of the almost 1,500 lithic artifacts were concentrated.

A circular hearth nearby is about 26 inches (66 centimeters) wide, set into older sediments and ringed by reddened soil and ash.

No finished quartz tools were left behind, which fits a classic workshop signature. People made blanks here, selected the good ones, and carried them away for use.

How scientists decoded the layer

Charcoal from the hearth yielded early Holocene ages using radiocarbon dating. This method measures the decay of carbon isotopes in once living material. The dates from different parts of the hearth agree, which supports a short, single episode of activity.

Specialists also used anthracology to identify the firewood as Detarium species, trees that are common in Sudanian savannas.

To cross check the environment, the team studied phytoliths, tiny silica bodies that plants leave in soils. Results point to an open savanna with grasses and scattered trees, wetter than the glacial period that came before.

What quartz tools reveal

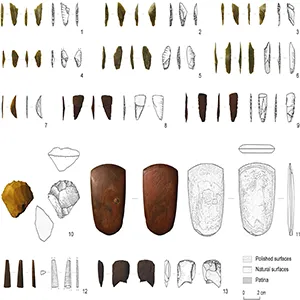

Two distinct blank types were produced with care. One set is broad, thick, and rectilinear, with straight, parallel edges.

The other set is elongated, narrow, and thin, often with an oblique tip suitable for mounting as standardized armatures.

“The strong investment in blank standardization from the extraction stage significantly reduced the need for subsequent retouching, which was rarely observed in the RBX-1 lithic assemblage,” wrote Pruvost.

Standardization signals skill, planning, and a desire for uniform parts that fit composite weapons.

West Africa in a changing climate

The workshop sits at the opening of the African Humid Period, when monsoon rains pushed north and savannas expanded.

Climatic studies show that these wet conditions fluctuated across northern Africa during the Holocene, reshaping water, vegetation, and human mobility.

Phytoliths and charcoal at RBX-1 agree with that broader picture. People were working in a grass-rich savanna with available wood and stable surfaces that protected small flakes from being washed away.

Comparisons across the region

RBX-1 is not alone, and the comparisons matter. At Fatandi V in the same valley, researchers reported stratified LSA layers with systematic bladelet production and microliths.

Fatandi V shows how chert was worked in short sequences that nonetheless aimed at consistent blanks.

Farther up the sequence, two Final Pleistocene sites, Toumboura I and Ravin de Sansandé, yielded microlithic industries dated between about 19,000 and 12,000 years ago.

Those assemblages emphasize small geometric pieces made from locally available stones like chert and quartz.

Ceramics appear early in the region, but not yet at RBX-1. Evidence from Ounjougou in Mali shows pottery before 9400 BC, tied to wetter conditions and new subsistence choices.

That timeline helps frame RBX-1 as a late aceramic LSA snapshot, even though pottery existed elsewhere.

Quartz tool skills and choices

The quartz at RBX-1 is unusually homogeneous, likely selected from nearby veins for quality. Cores were managed to keep convexities stable, so makers could pull off straight-edged, repeatable blanks with minimal waste.

Many flakes are small and angular, which is typical for quartz. The best products, however, hit narrow windows of geometry and thickness. That degree of control is hard to fake and shows learned technique passed within a group.

Everything points to a short visit focused on production. There are no postholes, bones, or piles of mixed trash, just the hearth, the debris ring, and the blanks that did not make the cut.

The rest of the tool kit likely traveled to where game was hunted or where tasks like hafting and maintenance took place. In other words, RBX-1 records one job in a seasonal round, not the whole camp.

Regional links with quartz tools

The team notes links between RBX-1 and sites across the Sahelo-Sudanian belt, where open savanna, rivers, and seasonal movement shaped technology.

Comparisons suggest shared habits in how small cores were prepared and how interchangeable parts were produced.

That does not mean everything looked the same. Forest zone sites farther south often show less standardization and different choices, which could reflect contrasting environments and cultural traditions.

Archaeology in West Africa has to work with rare, fragile layers. When one survives with a hearth, microdebris, and intact plant traces, it can sharpen timelines and test ideas about climate, mobility, and technology.

RBX-1 gives students of prehistory something that is usually hard to find in this region. It is a clean slice of activity, anchored in time and space, and tied into a growing regional map of people and practices.

The study is published in PLOS ONE.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way