Direct link found between the weather and the amount of sugar humans eat

When the air turns hot, your body shifts into cooling mode: you sweat from heat, you lose water, and your brain looks for fast relief, usually in the form of sugar.

Sweetness signals quick energy, and cold, sugary drinks or treats feel extra tempting because they promise two things at once – fluid to cool you down and sugar to perk you up.

Heat also dulls appetite for heavy foods, so sipping something sweet feels easier than eating a full meal.

Add bright ads and ice-cold displays by the checkout, and it’s no surprise that warm days nudge many people toward more sugar than they’d normally choose. But is this just observational bias, or is it a real thing?

Heat and sugar consumption

A new study looked at what millions of U.S. households actually bought in grocery stores from 2004 to 2019 and asked a simple question: when the temperature rises, do people end up taking in more added sugar?

The short answer is yes, and the increase shows up most in communities with lower incomes or less formal education.

The longer answer uncovers a demand-side ripple of climate change that most of us haven’t thought about: heat changes cravings and habits, and those shifts can widen health gaps unless we plan for them.

For every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit of warming, added sugar rose by about 0.7 grams per person per day, with the sharpest climb from roughly 68 to 86 degrees Fahrenheit.

That may not sound like much in a day, but across a season and a population, it stacks up.

Heat and sugar link

The project was led by Pan He of Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

She and colleagues paired long running scanner data from tens of thousands of households with local temperature, humidity, wind, and precipitation to isolate the temperature effect.

The analysis focused on retail purchases rather than restaurant orders, so it likely undercounts some items consumed away from home. Even so, the signal was clear in warmer months across many regions.

The temperature response was not linear at every extreme. The increase was strongest in moderate to hot ranges, while the very hottest days showed a flattening.

How temperature alters food choices

Beverages did most of the work. The extra sugar came mainly from sodas and fruit drinks, while frozen desserts added a smaller share.

Extreme heat can suppress appetite, which helps explain why the total increase slows on the most sweltering days. That kink does not erase the broader upward link between heat and added sugar.

Price movements did not drive the core pattern. When researchers accounted for food prices, the heat signal largely held.

Who feels the heat most

The effect was largest in households with lower income or less education, a reminder that socioeconomic factors shape both exposure and choices.

Higher income groups showed smaller changes, likely reflecting access to air conditioning, safer water, and steadier routines.

Patterns varied by background climate and work setting. People in cooler baseline regions and households with outdoor workers were more responsive to hotter conditions.

“What surprised us most was that the strongest increase in added sugar consumption occurred not during extreme heat, but within a relatively mild temperature range, between 12°C and 30°C,” explained Pan He.

This suggests that even moderate warming can significantly influence dietary behavior, leading to increased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and frozen desserts.”

What this means for health

Excess added sugar is linked to weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease, and average U.S. adults still take in about 17 teaspoons per day.

That baseline makes a few extra grams per day under future warming more troubling for those already at risk.

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends capping added sugars at about 6 percent of daily calories. That comes to roughly 36 grams per day for men and 25 grams for women.

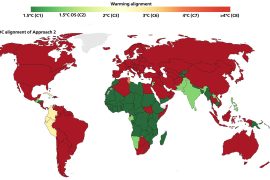

The study’s projection adds context. Under a high emissions pathway, the researchers estimate nearly 3 grams per person per day of additional added sugar by 2095, with the steepest seasonal rise in summer and fall.

Health burdens do not fall evenly. Communities with fewer resources already face higher rates of diet related disease, so a temperature linked nudge toward more sugar can widen gaps.

What can be done

Public policy can help. City level beverage taxes have been followed by higher shelf prices for taxed drinks and lower purchases of sugary beverages, as shown in a study from Berkeley back in 2017.

Clearer labeling and steady nutrition education can support better choices without adding cost. Water access matters too, especially in neighborhoods with unsafe pipes or limited fountains.

Climate adaptation plans should include diet. Cooling centers, safe drinking water, and employer protocols for hot days can lower the pull of sweet, chilled products when temperatures spike.

More research on sugar intake and heat

Restaurant orders remain a blind spot, and future work can test whether the same pattern appears in quick service and delivery data.

That matters for sweetened coffees, teas, and blended drinks that often carry substantial added sugar.

The team’s approach can extend to other countries and cultures.

Regions with popular sweet teas, energy drinks, or bubble teas may show different temperature thresholds but similar upward shifts during warm periods.

The study is published in Nature Climate Change.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way