Discovery in a forgotten rock changes everything we knew about Stonehenge

A forgotten stone from a 1924 dig is now steering a long running Stonehenge debate in a clear direction. New analyses of the hand sized Newall boulder point to people, not ice, as the movers of the monument’s smaller bluestones.

Researchers mapped the rock’s minerals and chemistry and matched it to Craig Rhos-y-Felin in west Wales, about 125 miles from Salisbury Plain.

The team also showed that its wear patterns and the wider landscape record do not support an ice delivery theory.

Why a palm size stone matters

Lead scientist Richard E. Bevins of Aberystwyth University guided the work that put this small clast under a big spotlight.

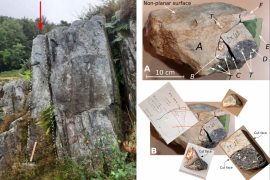

The boulder measures roughly 8.7 by 5.9 by 3.9 inches, was lifted during Lt Col Hawley’s 1924 excavations, and later archived with thin sections and sample records.

Its value is simple. As a stand alone piece with a clear excavation history, it offers a fair test for the human versus ice question that has followed Stonehenge for decades.

The team reports a bullet like profile but no glacial scratches. Surface abrasion fits burial and weathering after breakage, not grinding at a glacier’s base.

Tracing the Stonehenge rock to Wales

Under the microscope, its petrography matched the foliated rhyolite at Craig Rhos-y-Felin, including distinctive needle-like stilpnomelane and tiny titanite grains aligned with the rock’s fabric.

Those features, seen together, are unusual in Wales and line up with the proposed source.

Portable geochemistry sealed the case. Surface calcium was elevated by chalk soil coatings from millennia underground, but the deeper chemical fingerprint overlapped the Welsh outcrop and Stonehenge debitage.

The boulder’s taper echoes the tops of columnar rhyolite at the source. Its dimensions fit the buried Stone 32d stump at Stonehenge, which shares the same rock type.

Not the work of ice

Field surveys across Salisbury Plain report no till, erratic trains, or moraine ridges, and the regional glacial evidence shows major advances flowing offshore in the Celtic Sea. That pattern does not place an ice conveyor belt on the chalk plateau.

Around the monument, small fragments occur as sharp edged chips consistent with human dressing. A natural scatter of rounded cobbles has not been documented within the local two to three mile zone.

The Newall boulder itself shows wear that makes sense for weathering after a stone snapped. Claims of subglacial transport lack diagnostic marks and rely on assumptions the data do not support.

Quarries, dates, and a living landscape

Excavations at bluestone quarries at Carn Goedog and Craig Rhos-y-Felin revealed extraction platforms, wedges, and a trackway. Dating places activity in the centuries around 3400 to 3000 BC.

“The bluestones didn’t get put up at Stonehenge until around 2900 BC. It is more likely that the stones were first used in a local monument, somewhere near the quarries, that was then dismantled and dragged off to Wiltshire,” said Professor Mike Parker Pearson from the University College London (UCL).

Those field traces show people selecting and moving pillars in a busy Neolithic landscape. The Newall boulder’s match to Welsh rhyolite fits that wider picture.

Moving heavy stones without ice

Geochemical fingerprinting shows that most sarsens (silicified sandstone blocks) at Stonehenge came from West Woods about 15 miles away, an independent case of long distance selection and transport within the same monument.

If communities could marshal the labor to fetch multi-ton silcrete blocks, moving smaller rhyolite pillars was well within reach.

The bluestones weigh roughly 2 to 5 tons each, while the big sarsens average near 25 tons. That spread reminds us that the monument marries different rocks with different journeys.

Archaeology does not preserve ropes, sledges, or timber rails on chalk uplands, so methods remain inferred. Even so, the combined quarry traces, stone chips, and provenancing make a coherent case for human logistics.

Stonehenge still has secrets

The Newall boulder removes a key exhibit for the glacial transport argument. A hand sized clast once cited as an ice carried erratic now reads as a broken tip from a Welsh pillar.

With a secure Welsh origin, no diagnostic ice wear, and a match to a buried stump, the piece supports planned selection, extraction, and delivery by people. It shifts weight toward intention, not accident.

The wider bluestone assemblage also looks selective rather than random. A limited set of rock types, clustered sources, and consistent debris tell a story of choice instead of a scatter left by retreating ice.

This new work does not answer every question about routes or gear. It does tighten the link between Stonehenge and specific Welsh outcrops in the Neolithic centuries when people first raised stones on Salisbury Plain.

The study is published in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way