Early penguins were as big as humans and fished with long spears on their beaks

Most people picture penguins as black-and-white birds sliding across Antarctic ice or diving for fish. But the first penguins looked nothing like that. New penguin fossils from Aotearoa New Zealand show creatures with long, dagger-shaped beaks and bodies that came in strikingly different forms.

These early penguins were larger, stranger, and adapted to life in seas. They arose shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs and many large, marine reptiles. They may have capitalized on newly opened niches that were free from competitors or predators.

Their fossils reveal a period when birds were testing new ways of surviving, filling empty spaces in ecosystems, and setting the stage for the penguins we know today.

Penguin fossils in New Zealand

The fossils came from the Waipara Greensand formation in Canterbury, New Zealand. These rocks, about 62 to 58 million years old, preserve life that thrived soon after the mass extinction that ended the reign of non-avian dinosaurs.

Researchers think the absence of land predators gave penguins a chance to stop flying. That freedom may also explain why some species grew to the size of humans.

They developed unusual body shapes and features that allowed them to explore new environments, hunt more efficiently, and survive in changing coastal ecosystems.

Four new fossil penguin species

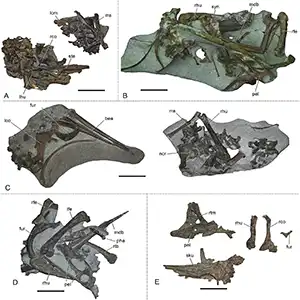

Gerald Mayr and his colleagues described four new penguin species from these rocks. The bones tell different stories, each one adding detail to the picture of early penguin life.

All the fossils reveal features that have never been documented before, expanding what scientists know about penguin anatomy.

One specimen had unusually long hind toes, a feature that might have changed how the bird balanced on land or swam in shallow water.

Another fossil preserved the most complete skull and beak ever found from an early penguin. That single discovery gave researchers an extraordinary chance to study head shape and feeding design up close.

Some skeletons suggest compact, streamlined birds, while others point to heavier, more robust forms.

In a world reshaped by extinction, penguins were already testing strategies for survival, adjusting their bodies and behavior to the opportunities offered in ancient seas.

Ancient penguin beaks

Tatsuro Ando of the Ashoro Museum of Paleontology in Japan, who was not part of the research, explained that fossils preserving beaks are extremely uncommon in penguins older than 23 million years.

Beaks can reveal important details about diet and so are crucial to understanding the lifestyles of early penguins.

Living penguins use short, thick, or curved beaks depending on whether they eat krill, squid, or fish. Early penguins were different. Their beaks were long and straight.

According to researchers, these birds probably speared fish with them, then tossed the catch in the air before swallowing it.

Penguin bodies changed over time

Penguins did not keep those spear-like beaks forever. About 20 million years later, their bodies shifted toward life spent almost entirely underwater.

With longer dives came changes in feeding style. Their beaks shortened, thickened, or became curved.

These new forms suited their aquatic hunting strategies better.

They allowed penguins to pursue different kinds of prey, dive to greater depths, and adapt more effectively to marine environments that were becoming increasingly competitive due to the presence of new predators.

New Zealand as cradle

New Zealand turned out to be a starting point for penguins. Gerald Mayr and his colleagues think the first species began here before moving on to Antarctica, South Africa, and South America.

At the time, New Zealand stood apart from many regions because it lacked land predators. That absence mattered.

Without constant threats on the ground, penguins grew larger than most birds and experimented with unusual shapes.

They tested new ways of moving, feeding, and surviving. The coastlines offered safety, while the surrounding waters provided plenty of food.

Together, these conditions created a perfect environment for trial and error. Over generations, these experiments shaped birds that would eventually spread across the Southern Hemisphere.

If New Zealand had not been so predator-free and resource-rich, penguins might have evolved along a very different path.

Modern penguin beaks

Penguins today fascinate people with their resilience and their unusual behaviors. Yet their story began with birds that looked more like spear-armed hunters than ice-dwellers.

The discoveries from Canterbury give us a rare look at those beginnings and remind us that penguins started their journey in warm seas, not frozen coasts.

These fossils bridge the gap between the world after dinosaurs and the penguins we know today. They show how survival, adaptation, and opportunity shaped one of nature’s most beloved bird families, connecting ancient spear-beaked hunters to the playful, diving birds that capture our imagination today.

The study is published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way