NASA can now detect a tsunami forming from space

On July 29, a powerful 8.8 magnitude earthquake rocked the ocean floor off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, triggering a tsunami that raced across the Pacific Ocean.

Though the waves didn’t cause much damage, the event did something just as important – it tested a new kind of tsunami detection system. And the system worked.

This system didn’t use underwater sensors or buoys. It didn’t rely on the usual seismic warning tools either. It looked up – to space.

Tsunamis shake air and sea

When a tsunami forms, it’s not just the water that moves. The surface of the ocean can rise and fall across huge areas, all at once. That giant motion pushes air above it.

The pressure waves shoot up into the upper atmosphere and keep going – thousands of miles per hour, all the way into the ionosphere. That’s where satellites fly and GPS signals travel.

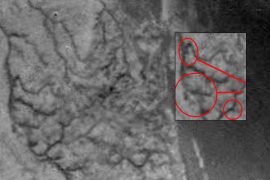

As those waves move through the atmosphere, they bend and stretch radio signals. You can’t hear or see it happening, but NASA’s new system can catch the signs.

GUARDIAN bends signals into warnings

The GNSS Upper Atmospheric Real-time Disaster Information and Alert Network (GUARDIAN) uses data from over 350 satellite ground stations spread across the world.

These stations are constantly communicating with satellites that make up what’s called the Global Navigation Satellite System – or GNSS – which includes GPS and similar systems.

Normally, ground systems fix distortions in these signals to get accurate location data. But GUARDIAN looks at those distortions instead. When it sees a certain kind of signal bending – the kind that happens after a tsunami shakes the sky – it starts pulling together a picture.

If it finds something suspicious, it notifies experts within minutes. And that’s exactly what happened during the Kamchatka earthquake.

Earthquake validates the new system

A day before the earthquake hit, the GUARDIAN team launched two new components of the system.

One was an artificial intelligence tool trained to spot important atmospheric changes. The other was a new messaging system designed to send alerts faster. When the earthquake struck, both parts kicked into action.

“GUARDIAN functioned to its full extent,” said Camille Martire, one of the developers of the technology at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The GUARDIAN system flagged signs of a tsunami just 20 minutes after the quake. It detected the signals of an approaching wave about 30 to 40 minutes before the water reached Hawaii and other locations around the Pacific.

“Those extra minutes of knowing something is coming could make a real difference when it comes to warning communities in the path,” said JPL scientist Siddharth Krishnamoorthy.

Tsunami detection in record time

GUARDIAN can detect changes in the atmosphere from a tsunami threat in near real time. Within 10 minutes of collecting the data, it can build a snapshot showing the effects of a tsunami reaching the upper atmosphere.

While it still requires trained experts to interpret the information, the system is one of the fastest tools available for tsunami monitoring.

Today, tsunami warnings mostly rely on seismic data and deep-ocean sensors. These methods work well, but they aren’t perfect. Some undersea quakes don’t cause tsunamis. And ocean sensors are expensive and spread thin across the vast ocean.

“NASA’s GUARDIAN can help fill the gaps,” said Christopher Moore, director of the NOAA Center for Tsunami Research. “It provides one more piece of information, one more valuable data point, that can help us determine, yes, we need to make the call to evacuate.”

Looking up to save lives

What makes GUARDIAN different is where it’s looking from. It’s watching the sky to learn what’s happening in the sea. It doesn’t care what caused the waves – earthquake, volcano, landslide, or even strange weather patterns.

It simply detects when something big has moved in the ocean and picks up the signs that ripple through the atmosphere.

This tool can sense evidence of a tsunami up to about 745 miles from a ground station. In the best-case scenarios, this could give coastal towns near these stations up to 1 hour and 20 minutes to prepare and evacuate.

Bill Fry, who leads the United Nations working group for tsunami warning in the Pacific, noted that this approach represents a major shift in how warnings can be issued.

“GUARDIAN is absolutely something that we in the early warning community are looking for to help underpin next generation forecasting,” said Fry.

GUARDIAN’s tsunami alerts

One big plus of GUARDIAN is that it’s not tied to one country. It uses open data from NASA’s global satellite network, making it available to other nations that need fast, reliable information.

“Tsunamis don’t respect national boundaries,” said Adrienne Moseley, co-director of the Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Centre. “We need to be able to share data around the whole region to be able to make assessments about the threat for all exposed coastlines.”

The Kamchatka event didn’t destroy buildings or flood towns. But it showed how much time a few extra minutes can buy when you’re racing against a wall of water. And it proved that a system watching the sky can help protect what’s on the ground.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way