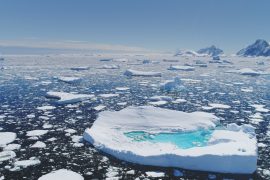

Polar ice is melting fast, and there is no current technology that can stop it

Polar ice is rapidly vanishing in both Antarctica and the South Pole, and the world keeps circling back to the same question: Can we use technology to stop it?

A new review takes a hard look at five of the boldest proposals for slowing polar melt – and comes back with a clear answer: not yet, and maybe not ever.

The stakes are rising fast. In 2025, Arctic sea ice hit its lowest winter maximum on record, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

That trend highlights why people keep dreaming up big fixes – and why scientists are now asking tough questions about whether those fixes could actually work.

Led by Professor Martin Siegert of the University of Exeter, the team evaluated the five ideas against six yardsticks: effectiveness, feasibility, scale and timing, environmental risk, cost, and governance.

Their conclusion is sobering – especially for the Arctic and Antarctic, where even small missteps can cascade into major problems.

Big ideas, bigger costs

The five ideas are simple to list and hard to pull off. They include stratospheric aerosol injection, which means spraying reflective particles high in the atmosphere, and seabed curtains to block warm currents from ice shelves.

Other ideas are sea ice management by boosting albedo with beads or by thickening ice, basal water removal under glaciers, and ocean iron fertilization (OIF) to stimulate plankton that carry carbon to the depth.

Cost alone should make readers pause. This analysis estimates that an 80-kilometer (about 50-mile) sea curtain would cost roughly 80 billion dollars over ten years. That figure comes before ongoing maintenance and unforeseen impacts are counted.

“Mid-century is approaching, but our time, money, and expertise is split between evidence-backed net zero efforts and speculative geoengineering projects,” said Professor Siegert.

Aerosols can’t save the polar ice

Stratospheric aerosol injection sounds straightforward: add particles like sulfur dioxide high in the stratosphere to reflect sunlight.

Over the poles it runs into physics, since winter darkness removes sunlight for months and cold-season circulation flushes aerosols out faster.

Even when the sun is up, snow and ice already reflect a lot of light, which weakens the effect.

The review also flags known risks, including ozone loss, shifts in rainfall, and the chance of rapid warming if injections stop after years of masking greenhouse heating.

Thicker ice plan falls short

One attention-grabbing idea is to scatter tiny hollow glass microspheres over first-year sea ice to reflect more light.

A 2022 paper calculated that roughly 360 megatons of beads per year would be needed and found the beads can darken some surfaces enough to accelerate ice loss.

Support for that approach also sagged outside the lab. A 2025 announcement from the Arctic Ice Project said the nonprofit was winding down after ecotoxicology tests raised potential food web risks.

What about thickening sea ice by pumping seawater onto the surface so it freezes?

The review points out a practical wall here too, since it would mean deploying and maintaining huge numbers of devices across drifting, breaking ice in brutal conditions for years.

Glacier pumping hits hard wall

Speeding glaciers depend partly on water at the base that reduces friction. Drilling through miles of moving ice and pumping out subglacial water across wide areas are a massive challenge.

Keeping the holes from freezing shut demands power, logistics, and precision that exceed current polar field capacity.

Fertilizing the Southern Ocean with iron to grow more plankton has been tested many times. A policy brief notes that only one ship experiment – the European Iron Fertilization Experiment – saw strong carbon export to more than 9,800 feet, where storage could last centuries.

It also found that nitrous oxide produced during remineralization can offset 5 to more than 40 percent of any carbon gains.

Even if results looked better, governance would still be a hurdle. The London Convention’s 2013 amendment restricts large-scale ocean fertilization to legitimate research, not carbon markets.

The review adds that the Antarctic Treaty System would require strict environmental review for most polar interventions.

Harsh realities of polar ice testing

Polar work windows are short, travel distances are long, and storms and sea ice can cancel whole seasons.

That is before counting iceberg hazards, darkness, and the difficulty of powering heavy equipment cleanly without leaving black carbon on the snow.

Scale also defeats many of these ideas. The ocean and ice do not respect neat borders, so diverting warm water from one polar ice shelf can steer it toward another.

Slowing one fast-flowing glacier can also redirect stress or subglacial water and speed up a neighbor.

Cutting CO2 still works best

The most reliable lever we have is still cutting carbon dioxide quickly.

The review emphasizes that temperatures tend to stabilize within about two decades after net-zero CO2, which slows the drivers of polar ice loss and gives ecosystems and communities a fighting chance.

Protecting polar biodiversity and local livelihoods also means expanding and enforcing strong protected areas.

It also requires improving monitoring and supporting Indigenous knowledge and leadership in the Arctic. These steps reduce harm now without adding new risks to already stressed systems.

The study is published in Frontiers in Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way