Soccer heading linked to changes in brain folds

Frequent heading in amateur soccer is linked with microstructural changes inside the brain’s folds. Those changes also track with slightly poorer scores on memory and thinking tests. The results point to an association, not proof of harm, but they flag a vulnerable layer that may reveal early injury.

Led by Michael L. Lipton, MD, PhD, at Columbia University, a new study focused on how everyday soccer might affect the brain in non-professional athletes. The authors stress that the findings are observational and cannot prove cause and effect.

“While taking part in sports has many benefits, including possibly reducing the risk of cognitive decline, repetitive head impacts from contact sports like soccer may offset those potential benefits,” Lipton said.

“Our study found that people who experienced more impacts from headers had more disruptions within a specific layer in the folds of the brain, and that these disruptions were also linked to poorer performance on thinking and memory tests.”

Soccer heading and brain impacts

The researchers enrolled 352 amateur soccer players, average age 26. For comparison, they also included 77 athletes in non-collision sports, average age 23. All participants reported their soccer activity for the prior year so the team could estimate head impacts from heading.

Players were then grouped by heading frequency, from the lowest exposure to the highest. Self-reports suggested a wide range of exposure. The highest group averaged about 3,152 headers per year.

The lowest group averaged 105. While any self-report can be imperfect, the spread provided a way to see whether brain measures varied with estimated impacts.

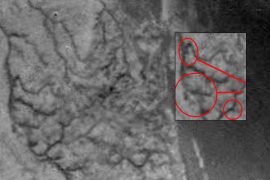

Through advanced brain imaging, the team focused on juxtacortical white matter. This is the thin layer of wiring that runs just beneath the brain’s gray matter in the cerebral cortex. In simple terms, it sits in the creases and ridges and carries signals between nearby cortical areas.

The scans tracked how water molecules move within that tissue. In healthy, well-organized white matter, water tends to move in a more orderly way. When the structure is disrupted, that movement looks more disorganized.

What the scans revealed

Compared with the low-heading group and the non-collision athletes, players in the highest heading group showed greater disruption in this juxtacortical layer. As estimated headers increased, the organization of water movement declined.

That pattern suggests worsening microstructure in the tissue lining the brain’s folds. The orbitofrontal region – just above the eye sockets – stood out. Disruptions there partially explained the link between repeated heading and lower cognitive scores.

Participants took standard tests of thinking and memory. Players who performed worse tended to have more disorganized water movement in the juxtacortical white matter.

The relationship does not prove that one causes the other. However, it does show that the brain changes and test scores rise and fall together in a meaningful way.

Why the folds may be vulnerable

The cortex folds to pack more brain surface into a limited space. That creates many short, local connections running through the juxtacortical layer.

Repetitive, low-level impacts might stress this thin wiring over time. If so, measuring this layer could help detect subtle injury earlier than conventional scans, which often look normal after mild impacts.

The research cannot prove that heading caused the changes. The heading counts were based on memory, which can be off.

Other factors – sleep, stress, or prior injuries – could also play a role. Still, the association is consistent and points to a specific, testable target for future studies. Larger, longer studies that track players over time and include objective head impact sensors will be key.

Needless impacts of soccer heading

“Our findings suggest that this layer of white matter in the folds of the brain is vulnerable to repeated trauma from heading and may be an important place to detect brain injury,” Lipton said.

“More research is needed to further explore this relationship and develop approaches that could lead to early detection of sports-related head trauma.”

Amateur players who head the ball more often show measurable differences in the brain’s thin white-matter layer along the cortex folds. Those differences also align with slightly lower performance on thinking and memory tests.

The results don’t prove harm, but they highlight a sensitive brain region that may help detect trouble earlier – and they raise practical questions about how to keep the joy and benefits of soccer while reducing needless head impacts.

The study is published in the journal Neurology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

News coming your way